Anti-Fascist Movies: Watch and Reflect

Note: On February 7, Trump announced that he was taking over the Kennedy Center in Washington DC. Not surprising, controlling the arts that has long been a dream of reaction. This calls to mind the ban Hitler imposed on literary criticism -- an anti-Semitic measure (Jews can “critique but cannot create” was a trope repeated in various forms ad nauseum in those years) to be sure. But it also exemplified the essence of the fascist approach to art: if it is not immediately comprehensible, then it is subversive. Put in other terms, critical thinking is itself subversive. The manifestations of that are visible everywhere today, most vividly in renewed book bannings, rewritten school curricula, repression of sexuality (which fits nicely with permissiveness toward sexual assault) and, of course, suppression of critical race theory (that word, "critical," does it everytime).

By contrast, anti-fascist films, anti-fascist art in all its forms, has one prime purpose: to encourage critical thinking, see beneath the surface, understand life in movement. The recent film about the assassination of Lumumba -- Soundtrack of a Coup d'Etat -- reminds us of the connection between fascism and colonialism and reminds us of the centrality of culture in the fight for freedom. Thoughts to keep in mind while watching the films noted below.

We are entering into a new period of reaction – and though the exact shape things will take in the years ahead are unknown, the immediate picture is indeed bleak. We face the all too real risk of authoritarian reaction, unfettered corporate power, a society rooted in stigmatization, violence, the crumbling of hard-fought rights.

That said, history does not repeat itself, politics doesn't unfold like a movie according to a director's script. People are not sheep, orders given aren’t always followed, can backfire on those in command. And capitalism being what it is, the logic of class antagonisms doesn't vanish just because those in power wills it to be so. Like the silent ghost of Christmas to come visions of the future tell of what may be, not what will be.

Critically, what we do matters. How we live, act, make a life for ourselves without giving in to resignation or bitterness are questions many are asking. Many movies have explored these dimensions for these are questions others have faced in times past – such as the films noted below -- all anti-fascist movies that reveal different aspects of how people have seen the possibility of change in the past during times when hope was hard to grasp. These don’t directly analyze the social or economic basis of fascism – though implied that is better addressed by books and articles. Nor do these dwell on its horrors (though those are never far from the surface) for what is most important is not what people with unbridled power can impose on us, but rather on what we can do as human beings, as political actors.

This list is far from comprehensive. For example, I left out documentaries though some, such as To Die in Madrid, The Sorrow and the Pity, The Battle of Chile, or Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence about Indonesia, are extraordinary works in their own right. Such films would be relevant for a much different kind of listing than that which I propose here. Moreover (and this should be self-evident) the list is limited to films I’ve seen. Many of them I haven’t viewed in decades, and though I admit to doing some fact checking, what mattered to me most in my choices and notes below are what I recall, the ways they remain alive in my mind.

Moreover, my focus is on Germany, Italy and the conflagration that engulfed Europe from through the two World Wars, partly as these provide the basis of current perceptions by fascists and anti-fascists alike and partly, by way of my personal background, as it is an era that informs by own understanding of the world. In particular, I don’t address the third wing of the “Axis” – imperial Japan, though its treatment of internal opposition in Japan, its war on the Chinese, its power over occupied Korea is comparable in key respects to the actions of Germany under Nazi rule. That is, unfortunately, simply a reflection of my sense of the inadequacy of older movies that I know addressing these (often with a racism toward the Japanese and a condescending sympathy toward Chinese, Filipino, and others fighting back). Perhaps, another list another time. That said, some films looking at other times and regions are noted for fascism is a worldwide phenomenon – and pedantic definitions of what fits or doesn’t fit a narrow definition of fascism can obscure more than clarify.

Of course, there are other good films that address these issues (Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator comes to mind), no doubt others could compile different movies of equal value. The point of what follows is simply to provide a starting point for reflection and discussion about the past to perhaps help shed light on our present and possible futures. The list is subdivided into categories that address certain recurring themes that I find of particular importance today. All those movies have been around for years, so I didn’t hesitate to describe plot points in my notes, and so please ignore my commentary if you want to watch each as if new.

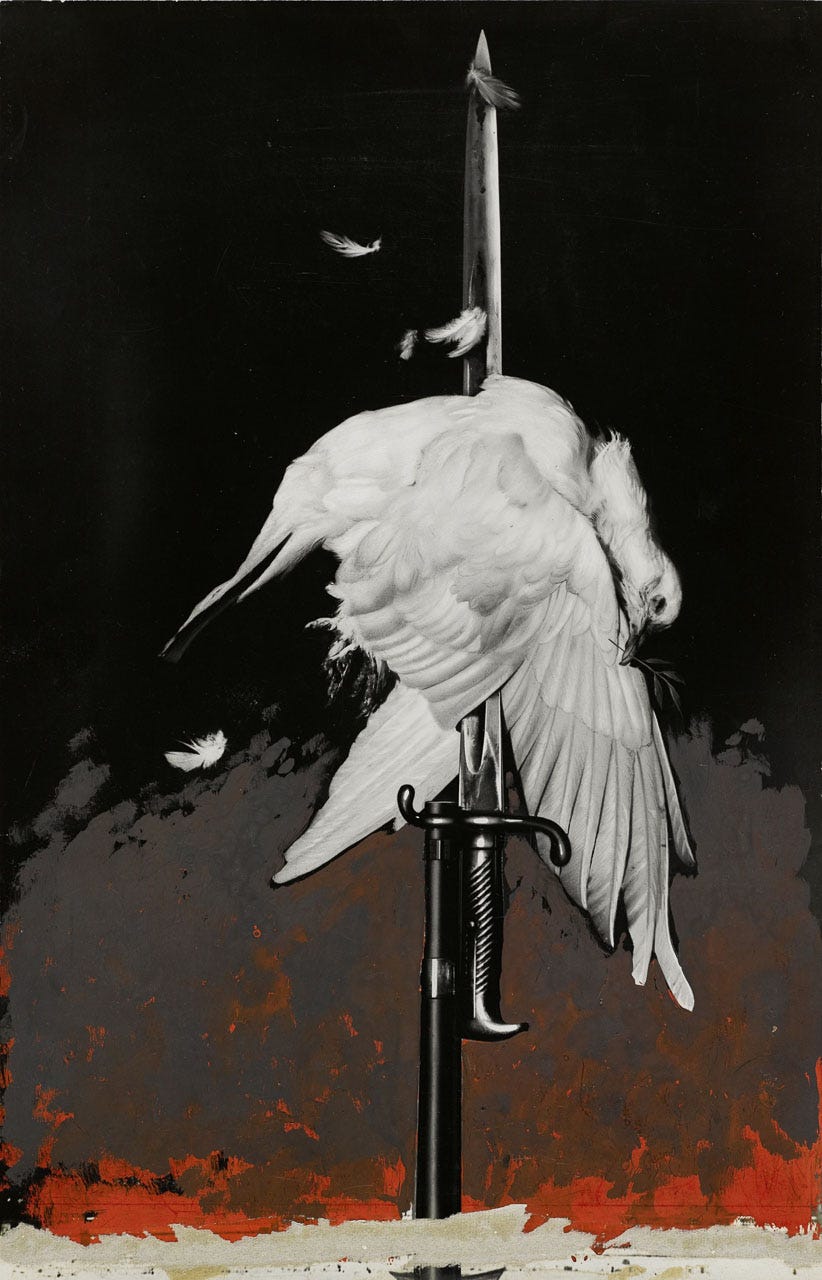

And as we engage with these films we should keep in mind always that fascism means war — war abroad, war against its own people, war for profit. That is the message of the John Heratfield montage and is the subtext to all the movies under consideration.

Hope and Fear

To understand fascism, one needs to understand what preceded it. The devastation of World War I, economic uncertainty via inflation and/or massive unemployment, intense exploitation at work, and a sense of society coming apart at the seams were in the background of all the disruptions of the 1920s and 30s. But with that as well was the advance of radical labor, of socialist and communist strength within the working class, of various upsurges that challenged the rule of capital. These, alongside the Russian Revolution which, however evaluated, created awareness that fundamental change is possible for all -- which instilled fear in ruling circles. In Central Europe the strength of revolutionary movements was palpable, but insufficient, hence not strong enough to overcome the attacks that were to come. Four films below touch on that legacy. The different emphasis in each – insurrection and works councils, factory occupations, building a revolutionary movement through mass actions and electoral activity, broad-based electoral engagements and movements rooted in coalitions, all tell a piece of the story, leaving threads that survived defeat, threads that, however frayed, remain perhaps to be rewoven, threads which fascism sought to cut off and burn.

Rosa Luxemburg -- Margarethe Von Trotta’s 1986 West German biographical film about Rosa Luxemburg (performed by Barbara Sukowa) depicts her life alongside the development of a working-class revolt and its defeat by the armed force of incipient fascism. Luxemburg’s life is illuminated through debates within the international socialist movement, her engagement as a revolutionary socialist in Poland/Russia and then within Germany. In doing so, the movie gives a sense of the controversies that would culminate in divisions that influenced subsequent left-wing working-class movements. So too, the film gives a sense of the organizing being done on the ground as in a scene of her campaigning in Polish-speaking parts of Germany for the Social Democratic Party (talking on women’s rights, the need to abolish the family and her smooth transition when a Polish worker with a very pregnant wife wonders about what that means in the immediate present). Her personal life is glimpsed too – especially her connection with Leo Jogiches – a romantic relationship at times, a close political relationship always, and later with Kostia Zetkin (her friend and comrade Clara Zetkin’s son) who was killed during the war.

Disagreements within the socialist movement hardened with the outbreak of World War I. Luxemburg played a central role as a leader of the minority of socialists who rejected militarism and nationalism, opposing the madness of war. Opposition to the war grew over time and that minority became a powerful force culminating in the German Revolution in 1918 -1919. Worker, peasant and soldier councils, analogous to those in Russia, rapidly grew in place of the discredited monarchy and posed a socialist alternative to a parliamentary system that would allow capitalism to stay in place. Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht (also on the Socialist left, a member of parliament and the public voice of opposition to the war) founded the Spartacist League as an illegal opposition organization to the war and from there helped found the German Communist Party early in 1919. The film touches on their disagreement – and reconciliation – over the uprising. The revolution was crushed by the “Freikorps,” armed detachments of soldiers, forerunners of Nazi storm troopers, in collaboration with the British and French governments as well as Social Democratic leadership. Luxemburg and Liebknecht had each been arrested many times previously. This was different – they were each brutally murdered (Jogiches was hunted down and murdered by German police a few months later as were numerous other Sparticist/Communist and anarchist workers).

The legacy of a revolution defeated and betrayed was two-fold – a weakened but still powerful revolutionary current rooted in large circles of a militant albeit deeply – and fatally – divided socialist movement up against business forces and reactionary circles fearful of that revolutionary fervor and determined to crush it. That culminated in fascism and Hitler’s ascendancy to power as the “better” alternative not only to socialism but to liberal democracy itself.

The Organizer (I compagni) – A strike in a textile factory at the end of the 19th century in Turin provides a background for the life and death struggle for the workers, providing a look at the Italian labor movement which was from its origins inextricably bound up with socialism. This 1963 movie, directed by Mario Monicelli, moves from a workplace accident due to exhaustion from overwork, a failed job action, followed by a strike. The workers initial action is spontaneous, driven by anger and desperation. The “organizer” (played by Marcello Mastroianni) – a high school teacher who had lost his job because of his socialist radicalism – helps them prepare for the battle ahead. The leadership, however, comes from the workforce itself as do the debates and arguments over which way forward. After months of intense conflict, including a violent confrontation with scabs, hunger drives the workers to accept defeat and they vote to return to work. The organizer urges them to occupy the factory as an alternative, a deadlock ensues which is broken when the injured worker raises his stump in support of action. The workers march on the plant, soldiers attack them, some are killed, the organizer arrested, others go underground. The film ends almost as it began with the workers trudging back to the factory for work.

But not quite the same, the worker initially most opposed to the strike has himself now become an organizer. The organizer who had had inspired and help prepare them for strike action has been nominated as a Socialist candidate for office – if victorious parliamentary immunity would mean his release from prison. Along the way the conflicts amongst the workers and the process by which they become cohesive is demonstrated through individual encounters. So too is the disparity shown. As harsh as their life is, a scene involving a Southern Italian family shows an even more desperate poverty. The conditions of life are highlighted by the black and white cinematography emphasizing the grayness of factory life.

Although socialism was a factor, one can see in this film how the Italian working-class centered its struggles at factories and at great landed estates, different from the movement in Germany in which political struggles predominated over labor action. The lines were drawn which would make factory occupations after World War I under socialist leadership the center point of struggle – and lead to Turin being the center of subsequent Communist strength (Antonio Gramsci was based there in 1919 and this influenced much of his subsequent thinking). But so too we can see in it the readiness to treat collective action by workers as criminal and to resort to state violence to put them down a precursor to Mussolini’s march on Rome and the support of business leaders and landowners that put him in power.

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World (Kuhle Wampe oder: Wem gehort die Welt?) – A 1933 movie set largely in “Kuhle Wampe” – a tent encampment for the unemployed on the outskirts of Berlin. Filmed on the eve of the Nazis takeover, it depicts the misery of mass unemployment in the waning days of the Weimar Republic. In counterpoint, it shows Communist youth trying to create something for themselves through sports, through nature and a sense of beauty, through discussion, as well as through political struggle. Filmed largely on location within the encampment, the film juxtaposes scenes of daily life around a thin plot line centered on a pregnant young woman and her friends, straddling the line between hope and hopelessness.

The first two segments of the film are titled (as might be done in the theatre) One Unemployed Man Less (about a suicide) and The Idyllic Life of a Young Person (eviction). The third segment is the film’s title -- taken from a line from a song written by Bertolt Brecht which asks the question: whose world is it? That anticipates an argument on a subway between middle class riders and the unemployed young militants. There is something tragic in seeing the film now – and thinking of the fate awaiting many of the film’s professionals as well as the non-professional extras who filled out the cast. The film itself was censored by the Weimar authorities, banned altogether by the Nazis.

Brecht wrote the basic script and the film – drawing from the montage films of Eisenstein and other early Soviet film makers as well as some of the radical concepts of theatre that he was then developing. The music was composed by Hans Eisler, a left-wing music composer with roots in the avant-garde. Ernest Busch, who played one of the leads, took part in the Spanish Civil War and, as a singer of workers songs gained wide renown during his lifetime. Another lead, Herta Thiele, was a well-known stage actress had previously starred in the film Madchen in Uniform, a lesbian-themed movie with an all-female cast. The Director, Slatan Dudow, was a Marxist film director, arrested by the Nazis. After his release went to exile in France, when France was occupied went to Switzerland (and then to East Germany after the war – as did Brecht, Eisler, Busch, and Thiele). Class is highlighted – the Nazis are not visible in the film, but the tension of lurking violence is everywhere. It is a glimpse of the world on the brink.

La Vie est a Nous (Life is Us) – This is a film made in 1936, directed by Jean Renoir (the painter Auguste Renoir’s son), for the French Communist Party in support of the Popular Front election campaign. The film is a mixture of acted sequences and documentary, depicting the hardships of daily French life, interspersed with footage of Communist leaders speaking at election rallies in support of the Popular Front. Reflecting the momentary hope of the Popular Front, the film was produced by a film collective organized by Renoir. An outstanding example of the project was the film The Crime of Monsieur Lange (workers taking over a book publishing house with an absent owner and running it as a collective) which also reflected the optimism and vision of the Popular Front. Central to the film is a question similar to that posed by Kuhle Wampe – to whom does France belong: the “200 families” or working people? Newsreel clips of Mussolini, Hitler and French fascists are followed by sequences showing deprivation and collective action – documentary and acted out footage interspersed.

As background, there was an attempted fascist coup in France in 1934. Unlike in Germany, the French Socialist and Communist Parties – together with the center-left Radical Socialist Party – came together to resist in the streets and then formed an electoral alliance which led to Socialist Leon Blum election as Prime minister. At the time, it gave hope that a way forward had been found to stop the rising tide of reaction which was spreading across Europe. That was the logic of the Vichy regime after France’s defeat in World War II, with fascists blocked in 1934 assuming power with the blessings of business circles and military collaborators.

Eve of Destruction

Fascism cannot be separated from the economic and political structures of capitalist society during periods of instability and crisis. But to say that and no more says very little – why such a virulent response at one time and not another, what does it mean to live in a society on the edge? More to the point, how do we understand people and culture who respond to the siren call of authoritarianism, of militarism, of chauvinism and racism? how can we understand the sense of loss such that people look backward not forward as a way out? The following films are attempts at answers.

Der Untertan – Wolfgang Staudte directed this 1951 East German movie based on a novel of the same name by Heinrich Mann (originally published in 1918). was made in East Germany in 1951, based on a novel on a Heinrich Mann published in 1918. The word itself is difficult to translate, the English versions of the film/novel have been variously known as The Loyal Subject, Man of Straw, The Patrioteer. A common translation of Untertan is the “underling,” it is better grasped as the “toady.” Best to think of it as defining those who welcome being kicked by those above them and enjoy kicking those below them – i.e. a personality type that gravitated to the Nazis.

The story is set in early 20th century Germany, focusing on a middle-class man and small manufacturer who is cowardly and opportunist, hiding his corruption behind worship of the Emperor – a successful strategy as he always manages to get ahead. The novel ends as his speech celebrating the unveiling of a statue of the Kaiser is interrupted by a thunderstorm; in the film that thunderstorm turns into allied bombing at the end of World War II. The satire of German culture was extremely divisive in the 1920s, the novel’s popularity on one side was matched by denunciations on the other (and, of course, it was banned once the Nazis came to power). The film was made in East Germany as part of an effort to understand the mindset that allowed fascism to come to power, it was banned in West Germany until 1957, then only permitted in censored form – the full version not released there until 1971 after the student movement forced questions of the past into the present.

Wolfgang Staudte had been an actor who remained working in film in Germany during the 1930s and 40s – his work on Der Untertan and the 1946 East German film, Murders Among Us, were part of his own process of coming to terms with his past. Mann (Thomas Mann’s brother) also wrote Professor Unrat about the self-degradation of German culture, later made into the film Blue Angel with Marlene Dietrich.

The Conformist (Il Conformista) – The 1970 film directed by Bernado Bertolucci examines the personality of someone whose search to “fit in” is an exemplification of the authoritarian personality, a personality that gravitates to fascism’s appeal. Set in the 1930s, the main character (performed by Jean-Louis Trignant, who appeared in several left-wing Italian films of that era) is a mid-level fascist official who is given the task of assassinating his former professor, a leading anti-fascist intellectual living in exile in Paris.

Flashbacks in the film look back to his early life – decaying wealth (and decaying personalities) of his parents, the trauma of being ostracized as a school boy for a gay encounter, the trauma of violence committed against him and by him at a young age. His response is to try and fit in, to be “normal,” the normality of following orders, the normality of suppressing feelings – of suppressed sexuality. It is that normality of repression which leads him to kill without remorse. And it is a mindset which facilitates the brutality of our times, that facilitates fascism. The film ends as the war ends – the “conformist” quickly changing his tune, fitting in, denouncing, unchanging.

The film is based on a novel by Alberto Moravia written at the end of World War II which, in turn, was influenced by the assassination of Carlo and Nello Rosselli in 1937, brothers and anti-fascist leaders of “Justice and Liberty (Giustizia e Liberta).”

Ship of Fools – The 1965 film (directed by Stanley Kramer with a screenplay by Abby Mann) is set on an ocean liner enroute from Mexico to 1933 Germany and evokes the sense of oncoming disaster from the interactions of passengers who are – for the most part – unaware of what lies ahead. The characters aboard the ship display the range of attitudes from arrogant Germans who believe in the “master race,” to other Germans who believe that such fools could never take power. Spanish laborers being deported from Cuban to forced labor in Spain, a wealthy woman facing imprisonment upon arrival for daring to help them after learning that her husband earned money from brutal exploitation, provide another lens on what was in the air. The others on the ship, obliviously wealthy, hangers on who grift, pimp or prostitute themselves, the lost and lonely underline the desperation in the air.

The moral center lies in the ship’s doctor, who fears slippage into accepting the unacceptable and discussions with his friend, the ship’s captain whose understanding of what he sees marks a deep cynicism. Two excluded passengers bond – a Jew returning to Germany believing that the worst won’t happen, and a dwarf whose narration begins and ends the film. It is the dwarf who names the other passengers as fools who can’t see what lies in front of them. The cast – for those who follow films – is extraordinary, including Vivian Leigh, Simone Signoret, Oskar Werner, Jose Greco, Jose Ferrer, a young Lee Marvin (as a former baseball player), and a young George Segal (as an aspiring – uncertainly socially conscious – artist) -- none fitting a simple pattern and thus making it more evident that blinkers on them foretold their inability to prevent the oncoming doom.

Katherine Anne Porter spent thirty years writing the novel of the same name, basing it on her observations while living in Germany on the eve of fascism (which she captured at the time in her short story, “The Leaning Tower,” written in 1931).

Cabaret -- Bob Fosse directed this 1972 film set in and around a musical hall in Berlin on the eve of fascism’s triumph. Liza Minelli as the night club singer and Joel Gray as the master of ceremonies perform in an atmosphere of despair and forced gaiety that mirrored the sensibility of a society coming apart at the seams. The poverty all around is hinted at, the growing anti-Semitism frames personal decisions as it is in the air, Nazi violence, though not yet pervasive, is never far away. None of this is depicted via polemic, but rather through the eyes of a gay academic (Michael York) teaching English at a boarding house to earn his keep. The relations between the borders, alongside the performances at the “Kit Kat Club,” provide a view of the contrasting and intersecting realities of the time.

Striking too are the two contrasting moments where we can see the appeal and the true face of fascist rule – a young man singing beautifully in a beer garden that “tomorrow will be our day,” with other patrons joining in all carrying a sense of almost innocence, of a kind of cleanliness (with all the dangerous implications that word carries), and then the night club itself, its performances moving from an ironic commentary to what is going on in society, to the irony becoming a reality. At the start of the film a Nazi is thrown out, by the end, the entire crowd are wearing swastikas – no pretense of innocence or cleanliness about them. Joel Grey recently pointed out the relevance of the night club sequences to the dangers we face today (see: https://www.broadwayworld.com/article/Joel-Grey-Says-Audiences-Should-Heed-CABARETs-Warning-20241124)

The musical is based on short stories (Berlin Stories) written by Christopher Isherwood in 1939 as a semi-fictional memoir of his time living in the dying Weimar Republic – and is itself well worth reading.

Living Under the Grip

Lives continued to be lived – some much as they had before, some experiencing a slow narrowing of what is possible in life, some turning to action, often reluctantly, when confronted with choices that could not be avoided. These films all depict daily life and the way political commitment and forms of resistance sometimes emerge when the realities of war or repression can no longer be ignored.

Christ Stopped at Eboli (Cristo si è fermato a Eboli)– Carlo Levi’s memoir of internal exile in a remote, rural part of Italy after arrest for his opposition political activity was made into a film directed by Francesco Rossi in 1979. A painter and a doctor, Levi observes and comes to know the people of the village where he is sent. The peasants living in unrelieved poverty provide a glimpse of the hollowness of Mussolini’s rule, as well as providing a counterpoint to the local elite and fascist officials, all of whom are themselves without ideology, concerned only with holding onto power.

Beautifully filmed and slowly paced, the movie is faithful to the memoir in giving a sense of the slow-moving nature of time. The movie begins as does Levi’s memoirs – the inhabitants of Eboli say that Christ stopped there, for it was too forlorn even for him. Although the community is isolated, the wider world impinges when some are sent to fight in fascist Italy’s war of conquest against independent Ethiopia (one of the opening acts of the Second World War).

What is depicted in the lives of the individuals he lives with is a kind of internal colonization, posing problems far different from those he experienced in the North (and thus questions of what to do after fascism that Levi was to explore in his political engagement and books in the years thereafter). Levi, a painter and doctor, was friends with the assassinated Roselli brothers and a member too of “Justice and Liberty.”). Three years after his release from exile Levi was rearrested and remained in prison until the overthrow of Mussolini.

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis ( Il giardino dei Finzi Contini)– This 1970 film by Vittori DeSica follows the daily lives of a family of Italian Jews in a prosperous northern city, Ferrara, as Mussolini’s evolving policies show the cost of complacency. The wealthy family, part of a small Jewish community, finds its world closing in as anti-Semitic laws are gradually passed. The film gives the texture of daily life as it becomes ever more constricted, the claustrophobia of an oppressive environment even as people continue to live out their daily lives of relationships, friendships, desires. Wealth and privilege protect them only for so long and then no more.

In the initial years of Mussolini’s rule, there were no restrictions on the Jewish community. That began to change as the power relationship between Germany and Italy changed. The story starts in 1938, when Italy first began to impose anti-Semitic laws, as Italy began to tighten restrictions on the Jewish community, then at the start of World War II with the disruption of everyone’s life, then to the middle of the war – as Italian losses mount – and all the Jews of Ferrara became subject to deportation. The combination of repression, war, anti-Semitism, are interwoven as people may having experienced it, step by step, rather than in one fell swoop.

The film is based on Giorgio Bassanti’s semi-autobiographical novel based on his own experience – he was one of the only Jews of Ferra to survive.

The Seventh Cross – this 1944 film directed by Fred Zinneman is based on a novel by Anna Seghers, an anti-fascist who lived in Mexico during the war (Mexico had a better record than most countries – a far better record than the United States – in accepting Jewish and political refugees fleeing the Nazis). She later became East Germany’s most prominent novelist. The premise of novel and film is that seven people escape from a concentration camp. Seven crosses are erected where their bodies are hung when caught – yet one “the seventh cross” remains empty. The film then tells the story of the remaining prisoner (Spencer Tracy) – a factory worker (and Communist – explicitly in the novel, implied in the film) – as he attempts to escape.

What motivates this film is that every encounter Spencer Tracy has confronts people with a choice – to remain passive in the face of Nazi repression or to act in ways to regain their own humanity. Doing so illuminates how the connection between people is the foundation of any form of resistance. All this takes place as the Tracy character slowly regains his humanity which he had almost forgotten as a concentration camp inmate – but throughout he remains largely passive, serving, however, as a catalyst for others to act. Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy play particularly critical roles as the link between personal morality and political action.

Zinneman was an Austrian Jew; both his parents were murdered at Dachau. Many of the smaller rolls in the film were played by other German refugees – including Helene Weigel, a leading German stage actress and Brecht’s wife, who plays a small role as a janitor and informer. Seghers was from Mainz (in Southwestern Germany) so much of the action in her novel (and in the movie) are set there. After the war she become East Germany’s most prominent novelist.

Alone in Berlin – This 2016 film is based on the true story of an apolitical working-class couple (Otto and Elise Hempel, portrayed, respectively, by Brendan Gleeson and Emma Thompson) living in Berlin who first begin to question fascism after their son is killed in battle in 1940. A scene in a factory and discussion sets the tone of anger that never leaves. Following that, they observe the mistreatment of an older Jewish neighbor who faces one restriction after another, making daily living almost impossible. After her suicide, the couple begin writing leaflets exhorting people to resist the Nazis in every way they can. Their actions are wholly personal, unconnected to any movement or organization. Moreover, there is never any suggestion that the leaflets have any practical effect. Yet the Nazis take the leaflets seriously, for any crack in their projection of invincibility and omniscience is danger. Eventually they are caught – by accident – and are both executed.

The story was memorialized by Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone, which was published in Berlin in 1946, a few weeks after he died. Fallada, a writer who, like most, didn’t emigrate – newspaper reporters, journalists, popular novelists and story tellers, wrote in German had little chance to earn a living abroad, so leaving was not an option – even people who were prominent and/or with strong connections with anti-fascist or refugee support organization, had a difficult time earning a living in exile. Such writers and journalists however uncomfortable or horrified by what was taking place could do little beyond an inner-emigration and, to the extent possible sticking to innocuous, apolitical themes, but that wasn’t always possible. Fallada, amongst such writers, at times felt compelled to do work commissioned by the propaganda ministry. Reading about the Hempels after their arrest – their resistance contrasting with his personal sense of complicity - he novelized the story while in a mental hospital, instead of writing a book Goebbels demanded of him. Every Man Dies Alone was published in 1946 some weeks before Fallada died. His early work, What Now, Little Man, written in 1932, had been a perfect evocation of Weimar on the eve of fascism – providing a similar look from a different perspective, as Kuhle Wampe.

And, quite unusual, a television production of the novel was produced, separately, in both West and East Germany. Alone in Berlin is a British production, directed by Vincent Perez.

Resistance to Fascism’s Wars

War brought out the full brutality of fascism. Beginning with Japan’s occupation of Manchuria and Italy’s of Ethiopia, aggression was accompanied by greater levels of internal repression. These movies, all made during or just after the war, address the Spanish Civil War, France and Czechoslovakia under occupation, resistance in Italy, the impact of the war in the Soviet Union and on wartime U.S. (and British) citizens -- the quality of the films vary, but they all touch on conflicting urges to ignore, collaborate or resist, and with that the personal choice to give in to loneliness or despair or to search for human connection.

Blockade – Made in 1938 while the Spanish Civil War was still raging (though nearing its conclusion with the fascist defeat of the Republican government but a year away). The film stars Henry Fonda as a Spanish farmer defending his land and the Popular Front Spanish government alongside British actress Madeline Carroll caught between spying for the fascists or supporting the Republicans. Carrol’s character is what moves the movie as her values change over the course of the film -- and curiously in life. A few years later, after her sister was killed in the London blitz, she stopped acting for the war’s duration, joined the Red Cross, working on the frontlines with wounded soldiers.

By way of background, Spain elected a Popular Front government (Socialist-Communist-Center Left liberal with some Anarchist support/tolerance) in 1936. A military coup backed by Italy and Germany was launched soon thereafter; while the US, Britain and France supported a non-intervention policy that only helped the fascists. The politics of the film were therefore not only centered on Spain – it was also and directly a plea to get the Roosevelt Administration to end its non-intervention policy – a policy that essentially gave Germany and Italy a free hand to support Franco’s overthrow of Spanish democracy. The film may be a bit melodramatic, itself a product of the times, though the film was nominated for an academy award for “Best Story”. Fonda’s portrayal is a precursor to his role as Tom Joad in Grapes of Wrath; the speech he gives at the end of the Blockade striking the same tone and sentiment as that of the Oakie migrant Steinbeck created – reflecting the connection between defense of Republican Spain and supporting the New Deal.

Notably, it was directed by William Dieterle, a German film director who left his country in 1930, seeing the writing on the wall. While in Hollywood, he helped get anti-Nazi Germans papers needed to enter the U.S. The screenplay was by John Howard Lawson, later one of the Hollywood 10 – arrested and imprisoned in 1949 at the start of the anti-Communist witchhunt, then blacklisted, this film was considered a prime example of his Communist “subversion.” Ironically (or perhaps that was the point of what was going on) Lawson had been a founder of the Screenwriters Guild. Dieterle, though with leftist sympathies, was not a Communist nor a political activist. Nonetheless, the attacks on Blockade at HUAC hearings meant that he found it increasing hard to get work in Hollywood and he eventually returned to Munich in West Germany.

This Land is Mine – Jean Renoir directed this movie in 1943 when living in exile in the U.S. The film focuses on two schoolteachers, living in the part of France under German occupation – Maureen O’Hara who embodies the spirit of resistance, and Charles Laughton whose character begins as an ineffectual coward who tries to close his eyes to the world around him. Laughton’s transformation – not by way of dramatic gestures, but by simple decency is at the core of the story. A third character (George Sanders) a railroad manager, shows the rationalizations, contradictions, costs of collaboration.

What is interesting about this film is that evil is not cartoonish, occupation politics are nuanced. The Germans want acquiescence by closing off the possibility of an alternative. Thus it is a defeat when they are compelled to resort to force (as with the execution of hostages), for it reflects their inability to gain acceptance – a truism reflected in the Laughton character. Anti-fascism during war involved arms, but in war or peace, key is gaining popular support. But even here, how people act, how they transform, has a great deal to do with class – a lens Renoir uses carefully to help give perspective on the choices people make.

The movie ends with a moving recitation of the “Rights of Man” by Laughton and then by O’Hara to school children. This has a particular meaning in the context of France as the French right-wing was never reconciled to the legacy of the French Revolution. Curiously, though not much remembered today, this film was one of the most popular of the wartime political films.

Hangmen Also Die – The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most brutal Nazis, second in command of the SS to Himmler, was the subject of this film, directed in in 1943 by Fritz Lang. Although the details of the assassination and subsequent repression were not fully known at the time the film was made ((virtually all the inhabitants of the village of Lidice were executed by the Nazis as retaliation), it does provide a close-eyed look at the nature of the personal and political choices people make as life or death decisions: to protect one’s family or one’s belief, to appeal to authorities or trust those opposed, saving someone in the underground at the expense of the lives of others – all are questions honestly posed within the framework of the film’s plot.

The complexity contained within the story reflects the influence of Bertolt Brecht who wrote the story and contributed to the screenplay (his only Hollywood credit during his years of exile in the US). The original screenplay was developed by John Wexley who was later to write one of the first books challenging the US government’s prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Composer Hans Eisler, another exile from Germany, won an academy award for the musical score. Lang was an Austrian who had been a prominent filmmaker during the Weimar Republic (Metropolis perhaps today his most famous) who left Germany after rejecting an offer by Goebbels to head up the film industry after the Nazis reorganized it. Instead, he organized an anti-Nazi film league in California (important as German influence in filmmaking and distribution had, before the war, led to self-censorship by Hollywood studios). The film is also interesting as showing the nature of German oppression in Czechoslovakia – which was a key industrial center – with the goal of exploiting labor and destroying Czech culture in an area they sought to fully “Germanize.”

Walter Brennan – later a character actor in countless Westerns -- plays a Czech university professor who had been a key figure in the nationalist movement that gained the country’s independence after World War I. His daughter’s (Anna Lee) movement from a simple act of opposition to attempted collaboration to determined resistance drives the film. A Communist underground is also depicted – trying to rescue the shooter, and, pointedly, trying to adjust policies as German measures begin to weaken the unity of the Czech people.

Open City (Roma città aperta) – Filmed on location in Rome in 1945, after the city had been liberated but before the end of the war Open City reflects the tension, anger and hope still in the air. Directed by Roberto Rossellini, this was the first of his “neo-realist” films that seek to recreate an atmosphere directly from experience to give authenticity to the story being told. The story is set a year prior, in 1944, when the Italian resistance was in the midst of a bitter last phase struggle against Italian fascists. Mussolini, who had been overthrown, was returned to power by the Nazis, the German army having occupied Rome to ensure his survival.

The film depicts the actions and arrest of a Communist resistance leader, a priest’s solidarity with him (and his own subsequent arrest/execution), the interplay between the two reflecting an attempt at the war’s conclusion to build the kind of popular unity that was lacking at the time of fascism’s rise. That search for unity has its counterpart in daily life and culture reflected by a priest officiating a marriage ceremony with an already pregnant woman (unthinkable in the Catholic hierarchy at the time – and unthinkable at any level in the U.S. in the 1940s) which a Communist militant prefers than having a government – i.e. fascist – official officiate.

Counterposed to that are the German officers and their Italian collaborators – for with the war almost lost there is no more pretense of an ideology, no more attempt to convince, only the decadence of those for whom power is about grabbing what you can today, to hold off a tomorrow for one further day.

The Fate of a Man – Based on a short story by Mikhail Sholokhov, the 1959 film depicts the losses suffered by the war through the story of personal loss. The movie chronicles the journey of a Soviet soldier, captured in battle in 1942, followed by brutal imprisonment, escape, return to battle and then a brief trip home where he learns that his wife and daughter and most towns people he knew were killed by German bombers. The story continues onto 1945 and the end of the war, when he learns that his son was killed in battle on the final day of the war. He returns home and bonds with an orphaned child who he adopts as his own.

The description seems melodramatic, but the telling is matter of fact, reflecting the experience of a country which lost over 20 million people in five years. Unlike Soviet productions in the years immediately after the war, this doesn’t stress huge battle scenes or the election of triumph – rather it is a statement of the horrors of war and of the necessity of human connection. His search is to overcome the loneliness and loss the fascist advance entailed and as such the story and film were extremely popular. German fascism was anti-Slavic, anti-Russian, anti-Communist so the war was a war of survival. The fight therefore was not only on the battlefield but also a fight to retain a sense of humanity. The 1957 Soviet movie – The Cranes are Flying – similarly and movingly focuses on individual loss and connection to survive the cruelty of war.

Sholokhov was one of the most significant Soviet writer during his lifetime. His public positions and activities within the Writers Union were always were in support of the Soviet leadership, while his fiction always reflected nuance and difficulties in everyday life that people faced; portraying the times with a realism that went along with his support of the system. The director, Sergei Bonarchul, later directed a remarkably well-done Soviet TV mini-series of War and Peace, a British film production of Waterloo as well as other films that depicted battle scenes never glossing over the horrors of war.

Lifeboat – Alfred Hitchcock’s 1944 movie explored the struggle against fascism via a contest between a heterogeneous group of British and American survivors on a lifeboat after their ship was destroyed by a U-Boat which was destroyed in turn. A German survivor from the U-Boat is also rescued setting up a conflict between a confirmed Nazi whose single-mindedness and ease of deception initially appear to give him greater strength than the other eight who have different perspectives and needs, frequently argue and thus fail to recognize the danger the German poses to them and their safety.

Yet they do – their differences, which also stem from illness, injury that they tend to (unlike the German U-boat officer who sees opportunity in the weakness of others) contributes to their seeming ineffectiveness. But their strength lies in that. The metaphor of democracy vs. fascism, resistance vs. occupation is present but not overdrawn, the strength of the film lies in its characterizations of people under extreme duress striving to survive.

To that end, the entire movie is set on the lifeboat, in black and white, with no background music, all reinforcing the claustrophobic atmosphere. There are women as well as men on board – including Tallulah Bankhead -- several are merchant seamen while others are wealthy passengers, reinforcing the theme of multiple voices in the closed setting. Canada Lee – one of the few African American stage and movie actors given substantive roles at the time – plays a significant role on the lifeboat (though the film can’t escape some stereotypes of the era). A protégé of Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes, Lee was later blacklisted when he refused to testify against Robeson before the House Unamerican Activities Committee.

Coming to Grips With the Past

After the war comes the battle for understanding – what happened, how did people behave. A coming to terms with history is, ultimately about coming to grips with the present. What do we remember, how does that inform choices we are making here and now so that other, better, choices may be possible later.

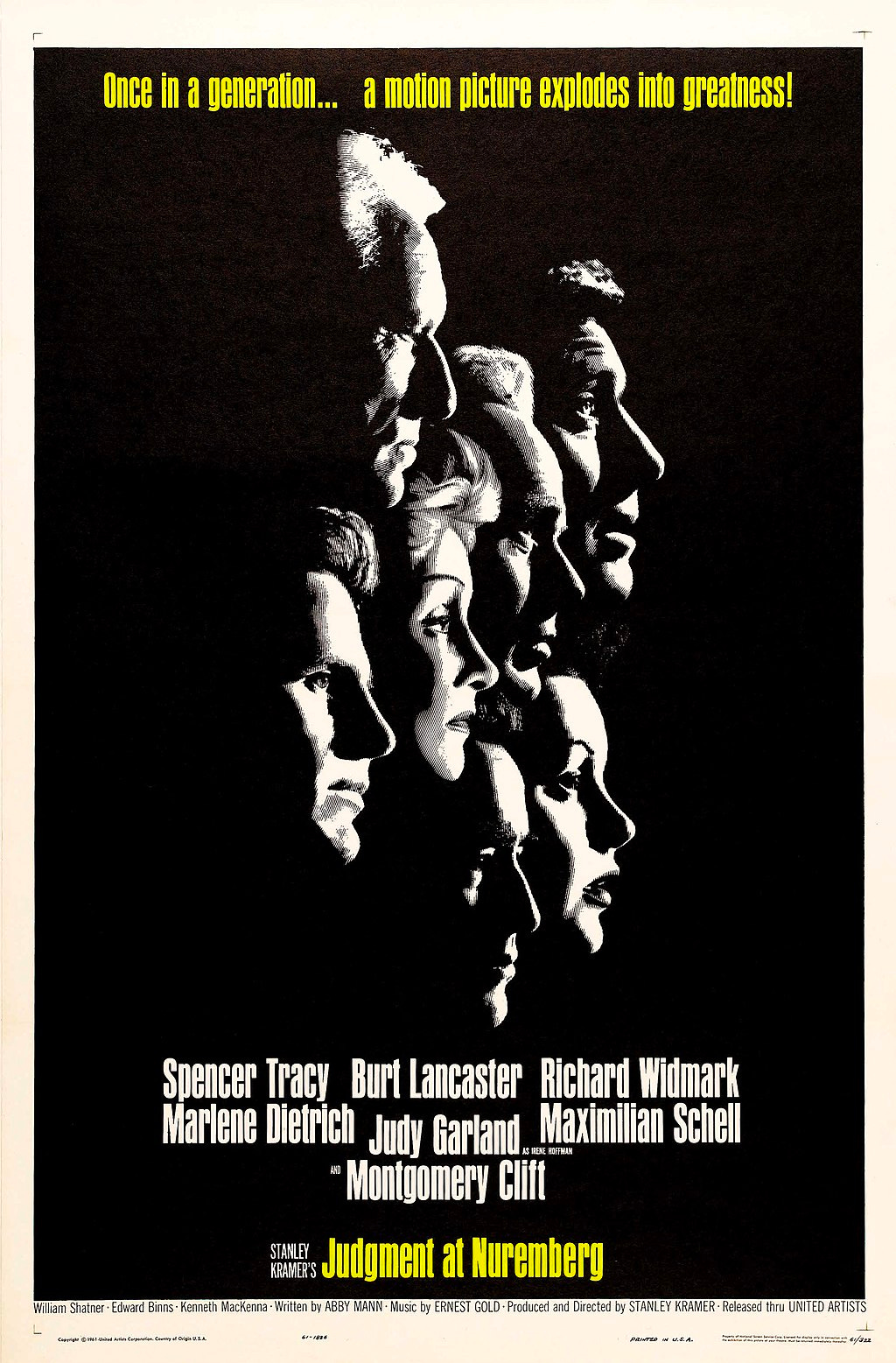

Judgement at Nuremberg – Based on actual transcripts, this fictionalized account of the Nuremberg Trials recreates in a courtroom setting the dynamic between complicity, silence, resistance. There were several rounds of Nuremberg trials to hold Nazis accountable for war crimes – all part of the same initiatives that led to the proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a foundational document of the United Nations. The movie focuses on trials condemning the complicity of judges in corrupting the legal system by their rulings after Hitler assumed power. Directed by Stanley Kramer, the 1961 movie (and, like Ship of Fools, written by Abby Mann) starred Spencer Tracy, Marlene Dietrich, Burt Lancaster, Judy Garland, Montgomery Cliff, and Maximilian Schell at a time when memories of World War II were still alive. Dietrich, a popular actress in Germany before Nazis ruled, rejected their offers to stay and came to the United States (and was later condemned in the post-World War II era by neo-Nazi groups for entertaining U.S. troops during the war). Like all the Nuremberg court cases, two forms of guilt are examined – the systemic guilt of fascism in power, the personal guilt of those who went along and were thus complicit in the system’s horrors.

The film presents, in grim detail, testimony of two cases (based on actual Nazi-era trials) in which judges ruled in accordance with “racial defilement” laws contrary to human decency and contrary to the actual facts (for opportunism was central to the fascist state) – a Jew executed for allegedly having sexual relations with his “Aryan” maid, a peasant (whose father was a Communist) ruled mentally incompetent and sterilized. Intense courtroom scenes reproduce the trauma of judicial replaying of malpractice. Footage of concentration camp victims, shown during the actual trials, is shown in the film.

The defense is given its due as their lawyer argues that the victorious allies all were complicit at various times as acting in concert with Hitler; defendants argue that they were simply following the laws on the state at the time as judges should, or that Germany was a bulwark defending Western civilization and culture against Bolshevism. And in the background, moving to the foreground, is the emerging Cold War, the US/Britian/Soviet alliance coming apart and with that western leniency toward former Nazis. Political acts, moral choice, legal ethics – everything we face and may face are on display.

The Nasty Girl – A 1990 West German film directed by Michael Verhoeven is based on the true story of a high school student (Played by Lena Stolze) who, as a research project, looked at her small Bavarian town’s history and its story of resistance to the Third Reich. What she discovered, instead, was evidence of overwhelming collaboration with the Nazis; a collaboration which had been written out of the town’s past. She continues her studies at university and discovers even deeper layers of complicity including the fact that her town’s elite had almost all joined the Nazis prior to Hitler taking power, that there were several concentration camps in and around the town and that all the local Jews had been expelled and had their property confiscated.

Additionally, the film depicts the increasing hostility in the town directed at her – from personal insults to physical assault to a bombing and death threats. All this puts pressure on her

marriage and personal life. The movie’s story is told both as part of a narrative and with jumps aside to her comments on what she is experiencing and observing – a kind of detachment that keeps the focus on the fact of the hypocrisy within the town (and by implication, more widely in Germany) rather than the narrative about “the nasty girl.” In a supreme irony, the town tries to silence her by honoring her truth-telling, an “honor” she rejects. It is thus not only a story of accepting fascism, but the story of conformity with the established order that is at the heart of the film.

Verhoeven had previously directed The White Rose – a 1982 West German film about Hans and Sophie Scholl (also performed by Stolze) – teenagers who opposed the Nazis and were executed for their resistance. The actions of the Scholls (and their fate) similar to that of the Hempels (depicted in Alone in Berlin), remind us that not everyone chose the path of silence or complicity. On the other hand, distribution of the film was delayed because West German law still recognized the “legality” of the Scholl’s execution – which had to be addressed before the film could be shown.

The Music Box – A 1989 film directed by Costas-Gravas is about a Hungarian (played by Armin Mueller-Stahl) living in Chicago accused of war crimes committed during the closing days of World War II. Jessica Lange plays his daughter, a defense lawyer, who wants to believe in her father’s innocence and comes by the end of the film to discover his guilt. What gives the story weight is that almost up until the end, she is able to legally “disprove” evidence against him be it the unreliability of witnesses’ years after the fact, implications that Hungary’s then existing Communist government wanted to frame anti-Communists, the lack of absolute proof. Yet, even as she is winning her case, each piece of evidence increases her own doubts. For the longest time, she resists drawing the obvious conclusions.

The crimes of which he is accused are not trivial – a leader of Hungary’s Arrow Cross fascist organization which supported collaboration with Germany during the war, he is accused of overseeing and participating in murders – committed with great brutality – of Jews, Roma, anti-fascists, the murders extending to children. A trip to Hungary reveals the depths of the crimes, a return brings the long-awaited proof. In consequence, she wants nothing to do with her father, will not allow her son to have anything to do with his grandfather. The personal decision to pursue the truth, however, whatever the familial consequences, is itself a critical component of resistance.

The screenplay was written by Hungarian-American Joe Eszterhas before he discovered that his father too had been in the Arrow Cross and participated in book burnings and anti-Semitic actions. He too broke off all relations with his father thereafter.

Playing for Time – A TV movie made in 1980 based on Fania Fenelon’s memoir, directed by Daniel Mann. A French Jew, active in the resistance during the war, she was arrested and sent to Auschwitz where a storm trooper recognized her as a well-known classical pianist. She, along with other classically trained women inmates were brought together to perform for the prison guard officers – the SS officers reveling in the culture, the women trying to maintain a precarious existence and survive.

Fenelon worked with Arthur Miller to bring the story to the screen. The film focuses on the moral guilt she felt, surviving by performing while other prisoners were being gassed or worked to death – survival which could feel like collaboration. Conflict and tension exists to amongst the orchestra members over who is and who is not permitted to be among the “performers” – a decision which is tantamount to life or death. The sense of guilt was in no way alleviated by the fact that they were themselves mistreated by the Nazis and their survival was never guaranteed. The camp was run by Josef Mengele – infamous for his brutal “medical experimentation” on women prisoners.

Vanessa Redgrave – a vocal opponent of Zionism and supporter of Palestinian rights – played Fenelon (a controversial decision when made, and an organized attempt was made to replace her. The other cast members as well as Miller all rallied to Redgrave’s defense). Jane Alexander played an imprisoned conductor. Progressive, multi-lingual folk singer Martha Schlamme – a Viennese born Orthodox Jew who managed to get out of Austria just before it was annexed by Germany – played as a small role in the film Apart from giving an unflinching look at their circumstances, it is a rare example of a film the about fascism with the focus on women.

Life is Beautiful (La vita è bella) – In 1997, Italian comedic actor Roberto Benigni directed and starred in a film about a Jewish waiter deported along with his son to Auschwitz in 1944. He strives to keep the boy alive by way of fantasy, pretending that imprisonment is a puzzle, a game the child must solve. The storytelling needed to help his son survive the camp, in its own way, speaks to the horrors if one puts oneself in the impossible shoes Benigini’s character adopts. So too it speaks in its own way to the nature of popular resistance. Moreover, the film’s beginning – the story of Benigni’s improbable love with a schoolteacher, his “robin hood” escapade taking her (Dora played by Niccoletta Braschi) away from an unloved fiancé, then their life together running a bookstore esn tablishes its theme – the beauty of life lies in human connection and love, not in striving not for wealth or power. The Benigni character is working-class as were most Jews in life, though not in films and especially not in films depicting Holocaust victims. Dora (she’s not Jewish) allows herself to be on the transport to Auschwitz as well and survives. Improbable too yet consistent with the film’s contrast between gentleness that belies strength and the blindness of oppressive power.

Some people were critical of the film insofar as the very nature of the plot presented a scenario incompatible with the grimness, the harshness of Auschwitz. Such, of course, is true but that hardly distinguishes it from other films or works of art that of necessity pick and choose aspects of the reality depicted. Moreover, films that revel in horror are neither enlightening nor necessarily truthful either. What gives this film meaning is the importance of imagination, of art in any form in times of suffering, for that is what gives individuals the ability to survive, to resist. Anyone who thinks that a correct political program in that circumstance would be sufficient to overcome the beast of unhindered violent repression fails to grasp the nature of fascism and resistance.

As to the truth of the film – Bruno Apitz in his book Naked Among Wolves novelizes a true story of prisoners at Buchenwald keeping a child alive and thereby keeping up their morale and their resistance which takes on a political character.

Jacob the Liar (Jakob der Lügner)– The GDR’s only academy award nomination was for this 1975 film is the story of a Polish Jew trapped in the Warsaw Ghetto who overhears a radio report that Soviet troops are advancing and Warsaw (and thus the Ghetto) might soon be liberated. The movie is based on a novel of the same name by Jurek Becker. Conditions in the ghetto were overcrowded, tightly constricted, transports out to death camps a regular feature. Hopelessness leading to suicides or desperate attempts to steal food that could lead to death were commonplace. When he tells the friend about German losses on the battlefield, hope is revived. However, to sustain that hope, he is forced to tell ever more lies thus putting himself at risk as well as the fear of what might happen if the illusions he has been telling are punctured. This includes a child whom he is trying to protect, and whose trust in him – and thus in his stories -- is absolute.

To continue he pretends he has a radio – punishable by death. Words spread, the Nazis hear about the nonexistent radio and search the Ghetto for it, adding a new risk for all trapped there. Jakob tells a friend that – apart from the first tale – all his stories are made up, and he decides to confess all. But his friend counsels him that his lies enable people to see beyond the moment and those encourages resistance in the form of personal survival – and reinforces attempts at survival that becomes communal. Yet, all the while, the number of transports to the extermination camps continue, eventually Jacob himself amongst those on the train.

A 1999 remake with Robin Williams sticks to the outlines of the story and is worth seeing in its own right, though it doesn’t quite depict the bleakness of the Ghetto to the extent of the East German film. As a side note – Armin Mueller-Stahl appeared in both the East German and U.S. versions.

Fascism: Other Times, Other Places

We focus on fascism in Italy and Germany in the 1930s-40s because that is the main reference point for fascists in our own country. But fascism has existed at other times, in other places and these too should be noted. None of these look the same, definitions do vary and while definitions are important to understanding what we experience and developing a political strategy, definitions can distort when used to undermine people’s understanding of the reality they are experiencing. For me, fascism means the protection of the power of capital and landowners through unrelieved suppression of democratic rights, civil liberties and free expression. Another criteria is that those struggling for freedom came to define their struggle as anti-fascist. Using that guideline, below are just a very few of the many possible films that serve to remind that the dangers facing the world now are part of a continuum that someday needs to be overcome at its roots.

Europe after the war: Following a military coup in Greece in 1967, it joined Spain and Portugal – all NATO members, all part of the “free world – ruled by fascist dictatorships.

Z – A 1969 film directed by Costa-Gravas was based on the 1963 assassination of an independent left-wing member or the Greek parliament, Giorgios Lambrakis (played by Yves Montand as the “Deputy”), focusing on the investigation of military and police officials who orchestrated his murder. The film proceeds in documentary style, showing the use of right-wing, impoverished vigilantes by the police to kill the “Deputy” and to make it look like an accident – at the site of a public peace rally attacked by vigilantes. A scrupulous prosecutor, an honest journalist, working-class witnesses willing to put their lives on the line come forward, revealing the conspiracy behind his death, implicating high-level military and police officers. And then the response: a military coup and fascist repression – mirroring the fate of Greece which fell under the heel of oppression from 1967 – 1974.

The movie begins the same way the Vassillis Vassilikos novel upon which it is based: with a high level military officer (the “General”) giving a talk to officers on germs: meaning the “disease” of communism, reflecting the extreme anti-Communism of the Greek establishment – reflecting divisions that broke out in a civil war after liberation from the Nazis and served as the first step of Cold War militarism by Britain and the U.S. Lambrakis’ assassination polarized an already polarized society, the massive popular anger at his death created the possibility of a center-left government which the coup was meant to forestall. The film ends with a list of the cultural expressions the military banned ranging from ancient Greek tragedy to modern pop music and including the word “Z” which means “He Lives.”

Costa-Gravas, was born in Greece but left to live in France after his father was arrested in 1946 as a Communist for his participation in the Greek resistance during and after the war and as part of the left during the civil war. The screenplay was written by Jorge Semprun, a Spaniard exiled in France after the defeat of the Spanish Republic. He later took part in the French resistance was captured and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Irene Pappas, who plays the “Deputy’s Wife” was exiled by the regime for her political activism and organized a cultural boycott of Greece. Mikis Theodorakis, who wrote the music for the film, had been arrested during the Greek Civil War as a member of the Communist-led partisans, was placed under house arrest immediately after the coup and then subsequently exiled. The film was co-produced by Algerian film director, Ahmed Rachedi.

South America – mid-1970s- 80s: Chile’s Popular Front government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by a military coup in 1973, Uruguay suffered a coup in 1974, Argentina in 1976, which together with the Brazilian and Argentinian military dictatorships made the entire Southern Cone of Latin America a field of repression – all linked to the imposition of neo-liberalism, all aided and abetted by the U.S. government, all designed to forestall any process of radicalism and social justice throughout Latin America. A “worthy” successor to the fascism which plagued Europe in the 1930s.

Burning Patience (Ardiente paciente) – The period of Popular Unity in Chile from 1970-73 was – like the Popular Unity government in Spain – rooted in working people finding a moment to express themselves in the context of a process seeking to transform economic and political structures of the country. From the first moment, the process was contested by all means possible and in Chile that meant a fascist coup in 1973. Burning patience, a 1985 film directed by Antonio Skarmeta (who also wrote the screenplay and the novel of that name) captures the hope and the pain in that process in the story of a postman in a small village where Pablo Neruda was living. The postman is in love, unable to find words to express himself, he asks Neruda – whose poetry about love, about beauty in nature, was as expressive as was his political poetry, helps him find his way – teaching him about metaphors, about the importance of naming.

All this in the background of the impending coup – the economic sabotage, the struggles to get supplies, yet the hopes which carry people forward. Those hopes, rooted in the simple things in life, built on naming what you see, understanding relations between what you know – that is poetry, that is what happens when two people fall in love, that is the basis for the striving for a better world. And that last is what fascism seeks to destroy.the coup which takes place at the end of the film, with Neruda dying then dead, with Mario (the postman) married to Beatriz being taken away everything gone – but not gone.

Neruda had been the Communist Party’s candidate for president in 1970, he withdrew in facor of the Socialist Party’s Allende. During the years of Popular Unity he served as ambassador to France, won the Nobel Prize, and remained a steadfast supporter of the new government. In 1994 an Italian version of the film – Il Postino was made – set in Italy in the 1950s when the Chilean Communist Party was outlawed and when workers struggles in Italy were being bitterly fought. Beyond that the plot follows the same outlines – and the relationship between words, poems, relationships between people, within society remains. Skarmeta had been forced into exile (in West Germany) after the coup, only returning to his homeland more than a decade later. Netflix remade Burning Patience in 2022 – though, from reviews, its focus on the love story seems to completely overshadow the politics – whereas in the original film and novel they are mixed as inextricably as is any of our personal life’s with the surrounding world at times of momentous change.

Argentina, 1985 –This 2022 film, directed by Santiago Mitre, recounts the trial of military junta leaders for the extra-legal murders and tortures that took place during the “dirty war,” in Argentina, in which tens of thousands were murdered by government decree. The film is based on an actual trial in which prosecutors called witnesses who testified to the outrages that took place and placed responsibility for them going up to the top of the chain of command.

The fascist government collapsed in 1983, the movie depicts the trials that took place two years later, uncovering secret prisons and torture sites around the country.

The film itself – based on actual prosecutions that took place after the Junta’s collapse -- shows the process by which people kept their eyes closed to what was clearly going on all around them, the way in which people learn to accept, the way in which the process of asking questions leads to more questions and that, in and of itself, to questioning. The courtroom testimonies also show the nature of unchecked repression and how once caught in its grip, there is no way out. And with that unchecked power as well comes sexual predadation – the abuse of women by prison guards a necessary complement to the human degradation entailed in the system. The contrast between the military’s leaders holding themselves up as guardians of the state, of law and order, of a superior morality are exposed in light of the lawless depradations inherent in the repressive system they installed.

The key in this film is that process, the rigid turning away from the truth, the opening up the truth and the ways differing individuals come to understand the nature of the society and system in which they lived. Argentina, far more quickly than other countries in Latin America suffering under the yoke of military fascism in the 1970s-80s, investigated and prosecuted – an outcome not unrelated to the strength of “Mothers of the Disappeared” – mothers and grandmothers whose children, arrested and murdered but not “officially,” so no bodies recovered – let alone the babies and small childred on the arrested “adopted” by military families and denied knowledge of who their actual parents were. Their weekly rallies began in 1977 at the height of the dictatorship. Although the film focuses on the prosecutor and his legal team, their role is noted. Fascism’s demise requires an accounting for without that, the human cost softens in memory.

Note 3: Fascism is, on one level, an outgrowth of colonialism – and in its later stages, colonial rule and fascism were virtually indistinguishable – as was evident in French treatment of Algerians, British of Kenyans, Portugal’s of Mozambique, Angola, Guinea-Bissau. The clearest example of that process was South Africa under apartheid – apartheid’s foes not hesitating to refer to the system as fascist.

Cry, The Beloved Country – A 1951 movie based on a novel written by Alan Paton in 1948 is a look at South Africa as apartheid was being imposed. The story focuses on a rural black minister (played by Canada Lee in his last film appearance) searching in the city for his sister – who has become a prostitute and his son – about to be executed for murder. Guiding him through urban pathways is a local minister (played by Sydney Poitier in one of his early roles). Their journey intersects with a racist white farmer, whose son – an anti-racist activist – was murdered by Lee’s son in a street crime. Though they lived in the same small district, the minister and farmer had never met prior to their coming to the city because of the realities of South Africa’s racial policies. They each learn and change from their experience but the hardships of South Africa’s racial policies are seen as the ultimate crime that imprisons all.

Paton was a political liberal, whose Christianity defined his politics, and he remained so throughout his life, even after the struggle intensified in the 1970s. Although South Africa under British rule was deeply racist and segregated, the legal imposition of apartheid after 1948 (a result of Afrikaners dominating the whites only elections that year) formalized a separate legal code for black and white meant that even moderate reforms became impossible – radicalizing opposition, intensifying repression. The movie was filmed in South Africa – and so Director Zoltan Korda had to tell immigration authorities that Lee and Poitier were his indentured servants.

The screenplay was uncredited as it was written by blacklisted John Howard Lawson, uncredited due to the blacklist. It was his next to last film, he remained blacklisted from Holywood the rest of his life. There was a subsequent remake of the film in 1995, starring James Earl Jones, one of the first made post-apartheid films (but the immediacy and passion in the 1951 version couldn’t be reproduced).

A Dry White Season – South Africa’s apartheid as its own form of fascism is best seen in this 1989 film. The movie is set in Soweto in 1976 when a rebellion by high school students renewed mass protest and set the stage for the continuous, escalating popular struggles that would culminate in the system’s defeat nearly 20 years later. The movie touches on how living a life of decency with eyes closed in a system where racial suppression is the absolute law becomes an impossibility. The plot centers on an escalating series of transformative events when a white school teacher’s gardener ‘s son and then the gardener himself are brutalized and killed by a system that allows for no recourse for blacks. The school teacher (Donald Sutherland) is transformed as realizes that the system he believed was based on lies. The ramifications for his family, his life are also damning when he discovers that those he loves resent him, hate him, for disrupting their secure life.

Euzhan Palcy, a French filmmaker originally from Martinique, was a pioneering black woman in the industry. Moreover, the film depicted scenes of life in Soweto (a center of black poverty and a seedbed of rebellion) and did not shy away from depicted the brutality of South African policy. It featured several South African actors (then in exile) who are shown as actors in the struggle not just recipients of outside support. Zakes Mokae (the school teacher’s driver) and Winston Ntshona (the gardener’s son) had acted in Athol Fugard’s anti-apartheid theatre. Ntshona was arrested by South African police and spent a year in solitary confinement.

Sutherland, Susan Sarandon and Marlon Brando (who came out of retirement to participate) all worked for far less than their usual pay to ensure the project made it to the screen. The film itself was based on a novel by Andre Brink – one of the very few Afrikaner (Descendants of Dutch-speaking Boers) writers supportive of the anti-apartheid movement.

Facing an Unknown Future

The example of South Africa might be the most relevant for our time. Certainly the system with its ordinary legal and parliamentary structures for a part of the population whereas other populations lack representation are subject to different laws and rules, and lack rights when those rules are suspended or non-existent has many parallels with Israel and its treatment of Palestinians. We can also see its relevance to the United States which has two significant populations that lack rights and legal protections afforded to others: undocumented immigrants, incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals – that is to say, millions of people. Legal discrimination, along with systemic discrimination leads to structural inequalities within the United States that exist within inequality that cuts like a knife between a small stratum on top (like those French 200 families) and everyone else. Precarity, insecurity, perpetual war, a moral vacuum in political leadership and a deep abiding alienation that runs through society (the world of those who live in Kuhle Wampe) – there too we see precursors of fascism in times gone by. Capitalism without restraint, capitalism fearful of egalitarian democracy, fearful of working people acting in concert that could impose restraint, that could call in the entire system into question can seize upon the fears generated in a society of disequilibrium to further reduce popular rights won in the past.

Looking back, however, doesn’t tell us what will be – the current wave of reaction will pose different challenges than what went before. Viewing these films, though, ought to remind us that what seems permanent – like the Nazi’s thousand-year Reich – fascist dictatorships can collapse like a house of cards. The reason: force alone can never keep any political or economic system in place indefinitely. The reason: people are capable of changing. While silence, acquiescence or collaboration may entice far too many, tides turn, experience and understanding create new awareness, action brings about new possibilities. As all these films, in their distinctive ways, affirm.

Perhaps in today’s world – in which dystopian nightmares seem more realistic than utopian dreams of the past -- fantasy becomes a way of addressing the challenges of overcoming fascism’s irrationality and violence than the more realistic movies noted above. Guillermo del Toro – Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and Pinnochio (2022) -- fantasy’s set in Franco’s Spain and Mussolini’s Italy perhaps speak more fully to today’s world than the more realistic films noted above. The meaning is everywhere the same: how to stand up for oneself and others when the outlook is bleakest, when one feels most alone.

This is the questions these movies pose – the answer well expressed toward the end of The Seventh Cross. One of the many people, many unknown to each other, helping the concentration camp escapee explains how each small action creates something bigger. He tells how he noticed that ants had gotten into a sugar bowl at the delicatessen where he works and had moved all the sugar, each one taking one grain, each simply doing their part and eventually, the bowl is empty. And then concludes: they can’t kill all the ants.

Each of these films provide pieces of a larger picture that includes all of us, each serves to underscore the simple fact -- what we do matters.